The paths of AI and video games have been closely intertwined over the years, running on parallel tracks with a common goal, and like many things in the world of tech, that journey began with one individual: Alan Turing. What’s more, if we look at the history of games and AI, we can learn a lot about the current state of both industries, and where gaming is going next!

THE EARLY YEARS OF ENEMY AI

We told a small lie before; modern gaming and modern AI both began with two individuals, not one. They were Alan Turing and David Champernowne (who would go on to become renowned as an economist, rather than a computer scientist) and in 1948 they began development on what was arguably the first chess computer algorithm. They called it Turochamp, and although the code was too complex to run on physical computers of the time, it played legal chess moves (something ChatGPT still cannot manage) and could search for possible moves up to three turns ahead. Sadly, Turochamp’s code has been lost to history, and only one recorded game played by it exists, from 1952. Turochamp lost, and AI would continue to lose chess matches versus humans until 1997, when IBM’s Deep Blue AI bested human world champion Garry Kasparov.

It took a long time for computer hardware to catch up with the ideas of visionaries like Turing and Champernowne, who had been forced to execute their code using a pencil and paper. It wouldn’t be until the 1970s that the concept of “video games” began to take shape, thanks to the early arcade games that began to rapidly replacing pinball in America’s public spaces. These would either require two human players – as with Atari’s Pong – or would have very basic and repetitive single player objectives with fixed difficulty levels, most notably with Taito’s early racing game, Speed Race. In 1978 Taito upped the ante with Space Invaders, which introduced the concept of scaling difficulty levels to gaming, with enemy attackers who moved faster and shot quicker as time passed, but it wasn’t until 1980 that their rivals, Namco, developed the game that would change everything.

LITTLE COMPUTER GHOSTS

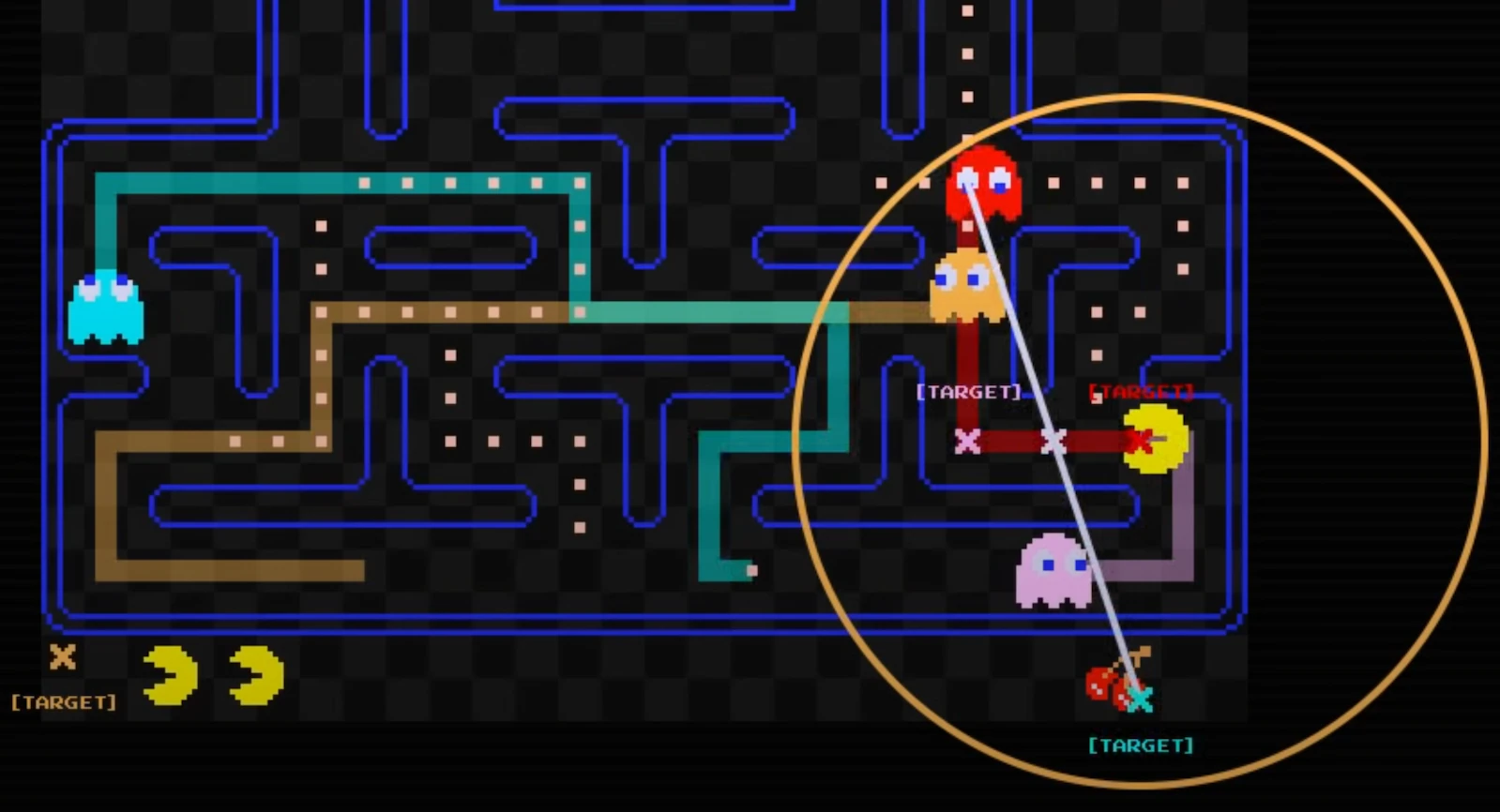

Space Invaders introduced the idea of computer controlled enemies, but Pac-Man gave them personalities. The four ghost antagonists – Inky, Blinky, Pinky and Clyde – all try to chase Pac-Man in different ways. Blinky (the red ghost) is the stupidest, but possibly the most effective; he just heads directly to where Pac-Man currently is by the shortest possible path. Pinky takes a similar but slightly more cunning approach; she heads for the tile where Pac-Man will be in a couple of seconds if he maintains his momentum. Inky (blue) and Clyde (orange) take far more devious routes, however. Inky bases his target position not just on Pac-Man, but also on Blinky, and aims to be on the exact opposite side from Pac-Man to Blinky at all times. Clyde, meanwhile, plays the long game, keeping his distance and hoping to corner his quarry from range. Although governed by simple mathematical rules, this combination of differing behaviors created a convincing impression that you were facing several thinking opponents, working in concert to corner the player.

1980 also saw the genesis of more complex – and less fun – enemy AIs in gaming, with the release of Computer Bismarck, widely recognised as the first war strategy video game, recreating the sinking of the Bismarck in 1942. The game featured an AI opponent (called Otto von Computer) who controlled the Nazi forces, and this was the first AI-controlled adversary in what are now called Grand Strategy games. Despite the grand title, the “AI” in these games operated on similar principles to Pac-Man’s ghosts, making decisions based on simple mathematical rules. While fun to compete against, these limited opponents were often predictable and exploitable, an issue that still faces developers of similar titles today.

Fortunately, much stranger game AIs were just around the corner. 1985 saw the release of Little Computer People, which invented the concept of the “virtual pet” some ten years before the Tamagotchi craze swept the planet. Little Computer People depicted a cutaway of a home, with a virtual resident who would go about their day, doing chores, watching television and reading the newspaper, oblivious to the player’s gaze. This was unusual in itself, but the game also had a special feature that was only available on the floppy disk release; every retail copy of the game had a random code written to a rarely-used sector on the disk, which the game would use as a seed to generate a unique and persistent “personality” for that specific Little Computer Person, one who would return every time you booted the game up. Customers who bought the game on the far cheaper and more readily available cassette format were not so blessed, rolling a new LCP every time they started the game.

GODLIKE INTELLIGENCE

As computing power began to grow, so did the ambition of games developers, and 1989 saw the release of one of the most ambitious games of all time, Populous, a title that would shape the gaming fashions of the next decade and radically alter what people expected from AI opponents in video games. Populous is renowned as the first “God game”, casting the player as a deity whose power is derived from their worshippers; more worshippers means more power. Unfortunately, you’re competing against other deities with similar ambitions, leading to strategic conflict, but unlike previous strategy games, Populous was not turn-based. The AI did not politely wait for you to wreak your havoc on its lands and forces, before returning the favor on its own turn; aggression and retaliation happened live and in real time, creating both frantic panic and a convincing sensation that the player was facing off against an intelligent adversary.

It would be another decade before the next big leap forward, which came from what was – at the time – a highly surprising source. In early 2001 Microsoft shocked the gaming industry by announcing its plans to compete with Sony and Nintendo in the games console market, an enormous gamble and a decision that was loudly mocked by industry insiders. The mockery grew even louder when it was announced that the launch of the new console – the Xbox – would be spearheaded by a first person shooter developed by Bungie, a well-regarded but obscure company best known for making games for the Apple Macintosh. Nobody predicted what would happen next: Bungie delivered Halo: Combat Evolved, an enormous critically acclaimed hit whose star attraction was not the graphics or the plot, but the enemy AI. Just as with Pac-Man, some 20 years earlier, the adversaries in Halo seemed to behave in concert, co-ordinating their movements to pin down the player. Unlike Pac-Man, Halo did not take place in a maze, but a fully realized three dimensional world, and its enemies took full advantage of cover, flanking opportunities and other strategic considerations, in a way which had never been seen before.

THE CURRENT GENERATION

Halo’s innovative enemies set a high bar that has rarely been bettered since, and gaming AI development in this century has shifted its focus to new challenges. One of the most interesting, successful and downright peculiar examples arrived in 2009 with the launch of Scribblenauts, on Nintendo’s handheld DS console, an unlikely platform for innovative AI products. Scribblenauts wasn’t just innovative, but years ahead of its time, with a gameplay loop that closely echoes large language models, almost a decade before Google launched the first LLM. Scribblenauts presents the player with simple puzzles, but complex solutions; by writing words on the screen using the console’s stylus, the user can summon objects to help tackle the problem. Scribblenauts dictionary recognizes 22,702 words, and through a limited form of AI it is able to recreate them onscreen using simple graphics, and also manage the myriad ways you can combine and use those objects. Once summoned, that object’s properties can be used to solve the problem: for example, the problem of an aggressive assailant can be solved using a Tyrannosaurus Rex’s biting properties. (Less drastic, more subtle solutions are also available.)

Scribblenauts married dictionaries and AI before it was cool, but more recent attempts to incorporate LLMs into gaming have run into difficulties. The best known is AI Dungeon, launched in 2019, which offered gamers a text-based fantasy adventure game run by an AI using large language models to drive the narrative forward, much like a DM in Dungeons and Dragons. Unfortunately, the nature of these narratives quickly turned toxic, with users reporting the LLM initiating discussions that weren’t just sexual in nature, but sometimes involved underage participants. OpenAI – who provided the GPT2 model for the game’s launch – stepped in and demanded proper moderation, which in turn sparked a backlash from users concerned about their privacy. Given these precedents, it’s unsurprising that other gaming companies have been slow to jump on the LLM bandwagon.

They’re far more keen about other forms of generative AI. Sadly, much of the attention in the gaming industry is now turned towards the modern vogue for character customization, with text-to-image services being deployed to allow gamers to design their own in-game items. These add little to the gameplay experience, but plenty to the developer’s bottom line, and as the internal economies of games targeted at young children often (but not always!) avoid scrutiny, this is a less reputationally dangerous way for big firms to incorporate AI in their games.

LATE GAME

So, where do we go from here? It seems that until the AI industry as a whole works out its issues around safeguarding, it will be difficult for developers to integrate the magic of LLMs into their games. However, many observers believe the benefits of doing so are going to be so great that we’ll be seeing these developments sooner rather than later. One such is veteran industry insider John Riccitiello, who gives an example of a player in FIFA taking time out from the football match to talk to a crowd member, and discovering all the details of that one NPC’s life.

It’s certainly a beguiling idea, but a cynic would question the gameplay benefits of these interactions with randomly generated strangers. They may also question Riccitiello’s motives, as he is the CEO of Unity, one of the leading game development platforms, and his enthusiasm for AI may well be because his firm has already rolled out limited AI gaming capabilities within Unity’s engine, which is installed on more than a billion devices worldwide. Cynicism aside, there’s little doubt that it’s here that we’ll most likely see the future of AI in gaming take shape, in the AI development tools that are being packaged in games development software like Unity and Unreal Engine, the tools which are used by both professionals and hobbyists alike to quickly create new videogame experiences. What they will create remains to be seen!